Special thanks to Vonda. This project was only possible with her help and generosity.

Throughout this term, I have primarily studied the life, correspondence, and published works of Vonda N. McIntyre, a Pacific Northwest science fiction author. McIntyre was born in Louisville, Kentucky on August 28, 1948 and has lived primarily in Seattle since her family settled there in the early 1960s. She is a 3-time winner of the Nebula Award and also won the 1979 Hugo Award for her acclaimed novel Dreamsnake.

After McIntyre spoke to our class in early November, I decided that I wanted to go further in-depth with my questions and conduct an interview with her to share with the class. You now have that interview, below. To develop my questions, I worked in the University of Oregon’s Special Collections, mainly in the Joanna Russ and Ursula K. Le Guin papers. It was a really interesting experience to be able to read through the letters of someone only a few years older than myself experiencing an earlier moment in history. McIntyre’s letters gave me a different, and better, perspective on many of the issues facing the country and young women in particular in the 1970s.

For additional background on Vonda, please see Kelsie’s excellent Wikipedia article: Vonda N. McIntyre. It provides a nice biography and bibliography.

Quintin – In your early 20’s, you left your PhD program in genetics at University of Washington and consequently began to write for a living. At that time, did you think writing would be your career, or something to do with your BS in Biology? At what point did you consider yourself a professional writer, as opposed to an amateur? What did that change mean to you?

Vonda – When I quit grad school, it was because I realized that as a research scientist, I made a very good SF writer. I already considered myself a professional writer. I had sold several stories, beginning in the summer of 1969, and had joined SFWA (Science Fiction Writers of America, now Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America, www.sfwa.org ), and had some interest in my first novel.

How did your relationships with other members of the sci-fi community change as you made the transition from fan/amateur to peer? (Especially Joanna Russ, Ursula K. Le Guin, James Tiptree, etc.)

I met Russ and Le Guin after I’d sold a number of stories.

Russ was one of my instructors at the 1970 Clarion Writers Workshop in Clarion, PA. Our relationship was generally that of teacher and student.

I met Ursula at the 1971 SFWA Nebula banquet in Berkeley, CA. After talking to her for about 37 nanoseconds, I asked if she would teach at the first Clarion West Writers Workshop in Seattle that coming summer. She agreed. (She was wonderful, and taught at all three sessions of the first incarnation of Clarion West, 1971-72-73.) She has always treated me as a peer, even when I was an ignorant pup, for which I’ll be eternally grateful.

I never met Tiptree. Our by-mail relationship began when Susan Anderson and I bought “Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” for our humanist anthology of SF stories, Aurora: Beyond Equality. She called me when she knew Tiptree was about to be outed. She was afraid people would hate her for not being Tiptree. I don’t know of anyone who changed their high opinion of Tip/Alli after the revelation. I was glad to know her as both Tip and as Alli.

You spoke a lot with Joanna Russ about your take on the feminist movement in the 1970s as a young woman. What do you feel has changed for women today, both at the university-level in general and in the sciences specifically? What about for beginning female authors?

As I’m neither an academic nor a scientist, I’m not qualified to answer the first question. There’s a good bit of discussion going on about the subject on various science and academic blogs, and I encourage you to search them out.

I would have hoped that things would have changed more, forty years down the line, but you still run into people who think there’s little or no room for women (or people of color) in SF — as writers, as readers, as characters. I thought we already fought that fight in the 1970s, and am appalled by the abuse directed at women SF writers and writers of color. This despite their having invigorated the field with original work and new perspectives. You have to wonder what some people are afraid of.

Something Kelsie pointed out was the parallel between your apartment in Seattle getting robbed in college (and your files taken) and Snake having her journal stolen by the crazy in Dreamsnake. Did real life inspire fiction here? How do things in your own life inspire your writing?

I don’t remember consciously making that connection, but it certainly could have been an inspiration. I don’t often base stories on specific events in my own life. I think events have to go through a fermentation process before they’re fit for fictional use.

As a young author, you didn’t hire a literary agent until after you won your first Nebula Award in 1973. Was this a conscious choice? I also saw that you continued to handle a lot of business affairs as an anthology editor and workshop organizer, even afterward. Do you like the financial management aspect of authorship, or was this a bit of Northwest DIY-ism?

At the time, a writer didn’t need an agent to submit short stories, and I believe that’s pretty much still true. The payment for short stories is so low, for most SF writers, that it isn’t worthwhile for an agent to negotiate a short story contract.

I negotiated the contract for my first novel myself. It ended up being a pretty good contract, partly because Fawcett Gold Medal, which published The Exile Waiting, had a decent boilerplate contract that didn’t require a great deal of negotiation, and partly because SFWA has a lot of information available for new writers about contracts. And also because the editor, Joseph Elder, was a good and fair editor.

Contracts these days are grabby and greedy. Often the most objectionable clauses are the least negotiable. Even with an agent watching your back, sometimes you have to say “No” and walk away.

When I was ready to submit Dreamsnake for publication, I was also ready to find an agent. I was lucky in my choice, Frances Collin, who still represents me.

I don’t particularly enjoy financial management. After Aurora, I didn’t edit another anthology till Nebula Awards Showcase 2004. I didn’t handle the finances of the first incarnation of Clarion West (1971-1973), and though I’ve taught at the second incarnation (1984-present), other folks run it — much more competently that I would have done.

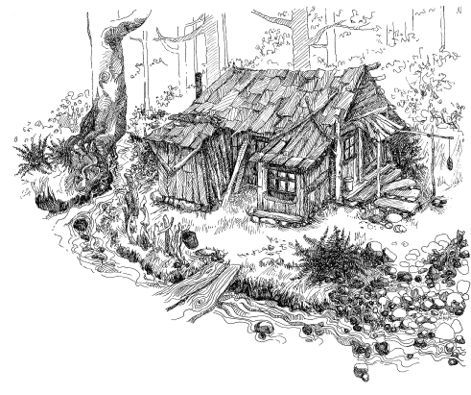

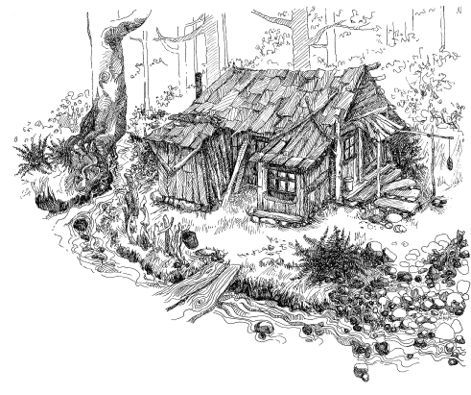

I grew up on the eastern side of the Oregon Coast Range, and I’m curious about how you were affected by your experience living at the Le Guin Cabin in Rose Lodge, Oregon? I understand you primarily lived there as you gained notoriety as an author and produced your first novel. How did the isolation of the PNW rainforest affect you?

I was very grateful to have the cabin to stay in. I enjoyed the solitude. If I was notorious as a writer I was, I’m afraid, unaware of that. I don’t believe I’ve been back to Rose Lodge since I moved out of the cabin and returned to Seattle and, after a year or so renting a Lake Forest Park mother-in-law apartment, bought a house.

by Charles Le Guin

More so than other authors we’ve read in our class, you have worked in Hollywood and in television. What motivated you to take your work in that direction? Were you influenced by Harlan Ellison? Could you talk a bit about the upcoming production of The Moon and the Sun?

I haven’t worked in Hollywood or in television. I wrote some teleplays when I was a pup — if I wrote an on spec teleplay, the series was sure to be cancelled the day after I finished.

I wrote two screenplays at the Chesterfield Company’s Writers Film Project (sponsored by Amblin Entertainment and Universal Studios) in Los Angeles, one of which turned into the novel The Moon and the Sun, which is scheduled to begin filming in the spring of 2014. They aren’t, however, using my screenplay. I can’t tell you anything more than you can find on the Internet, except that it’s going to be beautiful.

You may be thinking of the tie-in novels that I’ve written, mostly for Star Trek. They were great fun, but they don’t qualify as “working in Hollywood.” Most tie-in writers don’t hang out on the set or with the actors or the producers or the directors. Most tie-in writers for movies don’t get to see the movie before the book has to be finished. You’re lucky if you see a few publicity stills. (Any or all of that may have changed since the last time I wrote a tie-in novel.) The deadlines were usually pretty ferocious, so mostly what I did was write till I was too tired to work any more, sleep for a while, get up, and go back to writing.

I’ve blogged about tie-in work a couple of times. You might find the essays interesting, or at least amusing:

http://bookviewcafe.com/blog/2013/06/20/best-of-the-blog-writing-star-trek-novels-or-why-dont-you-get-a-morally-acceptable-job/

http://bookviewcafe.com/blog/2013/08/30/my-first-computer-osborne-i/

And of course the Starfarers Quartet started out as the best SF miniseries never made:

http://bookviewcafe.com/bookstore/book/starfarers/

http://bookviewcafe.com/blog/2009/10/18/casting-starfarers/

http://bookviewcafe.com/blog/2009/10/25/casting-starfarers-update/

http://bookviewcafe.com/blog/2009/12/27/the-starfarers-quartet/

http://bookviewcafe.com/blog/2010/03/21/starfarers-the-miniseries-cast/

Citations:

McIntyre, Vonda N. University of Oregon Special Collections (Eugene, OR), Joanna Russ Papers, “Correspondance with Vonda N. McIntyre, 1970-1988,” Box 8, Folders 18-25. Accessed October-December 2013.

McIntyre, Vonda N. University of Oregon Special Collections (Eugene, OR), Ursula Le Guin Papers [RESTRICTED], “Correspondance with Vonda N. McIntyre,” Box 22, Folders 11-14. Accessed November 2013.