Tag Archives: Vonda N. McIntyre

McIntyre Interview with Quintin Kreth

Special thanks to Vonda. This project was only possible with her help and generosity.

Throughout this term, I have primarily studied the life, correspondence, and published works of Vonda N. McIntyre, a Pacific Northwest science fiction author. McIntyre was born in Louisville, Kentucky on August 28, 1948 and has lived primarily in Seattle since her family settled there in the early 1960s. She is a 3-time winner of the Nebula Award and also won the 1979 Hugo Award for her acclaimed novel Dreamsnake.

After McIntyre spoke to our class in early November, I decided that I wanted to go further in-depth with my questions and conduct an interview with her to share with the class. You now have that interview, below. To develop my questions, I worked in the University of Oregon’s Special Collections, mainly in the Joanna Russ and Ursula K. Le Guin papers. It was a really interesting experience to be able to read through the letters of someone only a few years older than myself experiencing an earlier moment in history. McIntyre’s letters gave me a different, and better, perspective on many of the issues facing the country and young women in particular in the 1970s.

For additional background on Vonda, please see Kelsie’s excellent Wikipedia article: Vonda N. McIntyre. It provides a nice biography and bibliography.

Quintin – In your early 20’s, you left your PhD program in genetics at University of Washington and consequently began to write for a living. At that time, did you think writing would be your career, or something to do with your BS in Biology? At what point did you consider yourself a professional writer, as opposed to an amateur? What did that change mean to you?

Vonda – When I quit grad school, it was because I realized that as a research scientist, I made a very good SF writer. I already considered myself a professional writer. I had sold several stories, beginning in the summer of 1969, and had joined SFWA (Science Fiction Writers of America, now Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America, www.sfwa.org ), and had some interest in my first novel.

How did your relationships with other members of the sci-fi community change as you made the transition from fan/amateur to peer? (Especially Joanna Russ, Ursula K. Le Guin, James Tiptree, etc.)

I met Russ and Le Guin after I’d sold a number of stories.

Russ was one of my instructors at the 1970 Clarion Writers Workshop in Clarion, PA. Our relationship was generally that of teacher and student.

I met Ursula at the 1971 SFWA Nebula banquet in Berkeley, CA. After talking to her for about 37 nanoseconds, I asked if she would teach at the first Clarion West Writers Workshop in Seattle that coming summer. She agreed. (She was wonderful, and taught at all three sessions of the first incarnation of Clarion West, 1971-72-73.) She has always treated me as a peer, even when I was an ignorant pup, for which I’ll be eternally grateful.

I never met Tiptree. Our by-mail relationship began when Susan Anderson and I bought “Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” for our humanist anthology of SF stories, Aurora: Beyond Equality. She called me when she knew Tiptree was about to be outed. She was afraid people would hate her for not being Tiptree. I don’t know of anyone who changed their high opinion of Tip/Alli after the revelation. I was glad to know her as both Tip and as Alli.

You spoke a lot with Joanna Russ about your take on the feminist movement in the 1970s as a young woman. What do you feel has changed for women today, both at the university-level in general and in the sciences specifically? What about for beginning female authors?

As I’m neither an academic nor a scientist, I’m not qualified to answer the first question. There’s a good bit of discussion going on about the subject on various science and academic blogs, and I encourage you to search them out.

I would have hoped that things would have changed more, forty years down the line, but you still run into people who think there’s little or no room for women (or people of color) in SF — as writers, as readers, as characters. I thought we already fought that fight in the 1970s, and am appalled by the abuse directed at women SF writers and writers of color. This despite their having invigorated the field with original work and new perspectives. You have to wonder what some people are afraid of.

Something Kelsie pointed out was the parallel between your apartment in Seattle getting robbed in college (and your files taken) and Snake having her journal stolen by the crazy in Dreamsnake. Did real life inspire fiction here? How do things in your own life inspire your writing?

I don’t remember consciously making that connection, but it certainly could have been an inspiration. I don’t often base stories on specific events in my own life. I think events have to go through a fermentation process before they’re fit for fictional use.

As a young author, you didn’t hire a literary agent until after you won your first Nebula Award in 1973. Was this a conscious choice? I also saw that you continued to handle a lot of business affairs as an anthology editor and workshop organizer, even afterward. Do you like the financial management aspect of authorship, or was this a bit of Northwest DIY-ism?

At the time, a writer didn’t need an agent to submit short stories, and I believe that’s pretty much still true. The payment for short stories is so low, for most SF writers, that it isn’t worthwhile for an agent to negotiate a short story contract.

I negotiated the contract for my first novel myself. It ended up being a pretty good contract, partly because Fawcett Gold Medal, which published The Exile Waiting, had a decent boilerplate contract that didn’t require a great deal of negotiation, and partly because SFWA has a lot of information available for new writers about contracts. And also because the editor, Joseph Elder, was a good and fair editor.

Contracts these days are grabby and greedy. Often the most objectionable clauses are the least negotiable. Even with an agent watching your back, sometimes you have to say “No” and walk away.

When I was ready to submit Dreamsnake for publication, I was also ready to find an agent. I was lucky in my choice, Frances Collin, who still represents me.

I don’t particularly enjoy financial management. After Aurora, I didn’t edit another anthology till Nebula Awards Showcase 2004. I didn’t handle the finances of the first incarnation of Clarion West (1971-1973), and though I’ve taught at the second incarnation (1984-present), other folks run it — much more competently that I would have done.

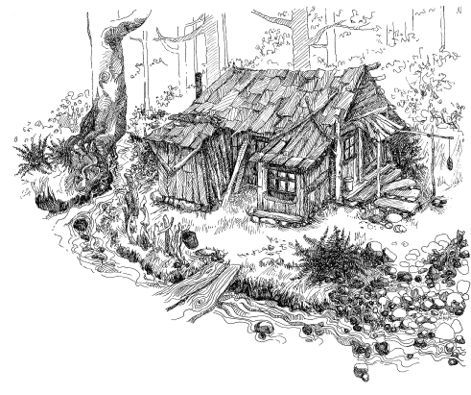

I grew up on the eastern side of the Oregon Coast Range, and I’m curious about how you were affected by your experience living at the Le Guin Cabin in Rose Lodge, Oregon? I understand you primarily lived there as you gained notoriety as an author and produced your first novel. How did the isolation of the PNW rainforest affect you?

I was very grateful to have the cabin to stay in. I enjoyed the solitude. If I was notorious as a writer I was, I’m afraid, unaware of that. I don’t believe I’ve been back to Rose Lodge since I moved out of the cabin and returned to Seattle and, after a year or so renting a Lake Forest Park mother-in-law apartment, bought a house.

More so than other authors we’ve read in our class, you have worked in Hollywood and in television. What motivated you to take your work in that direction? Were you influenced by Harlan Ellison? Could you talk a bit about the upcoming production of The Moon and the Sun?

I haven’t worked in Hollywood or in television. I wrote some teleplays when I was a pup — if I wrote an on spec teleplay, the series was sure to be cancelled the day after I finished.

I wrote two screenplays at the Chesterfield Company’s Writers Film Project (sponsored by Amblin Entertainment and Universal Studios) in Los Angeles, one of which turned into the novel The Moon and the Sun, which is scheduled to begin filming in the spring of 2014. They aren’t, however, using my screenplay. I can’t tell you anything more than you can find on the Internet, except that it’s going to be beautiful.

You may be thinking of the tie-in novels that I’ve written, mostly for Star Trek. They were great fun, but they don’t qualify as “working in Hollywood.” Most tie-in writers don’t hang out on the set or with the actors or the producers or the directors. Most tie-in writers for movies don’t get to see the movie before the book has to be finished. You’re lucky if you see a few publicity stills. (Any or all of that may have changed since the last time I wrote a tie-in novel.) The deadlines were usually pretty ferocious, so mostly what I did was write till I was too tired to work any more, sleep for a while, get up, and go back to writing.

I’ve blogged about tie-in work a couple of times. You might find the essays interesting, or at least amusing:

http://bookviewcafe.com/blog/2013/08/30/my-first-computer-osborne-i/

And of course the Starfarers Quartet started out as the best SF miniseries never made:

http://bookviewcafe.com/bookstore/book/starfarers/

http://bookviewcafe.com/blog/2009/10/18/casting-starfarers/

http://bookviewcafe.com/blog/2009/10/25/casting-starfarers-update/

http://bookviewcafe.com/blog/2009/12/27/the-starfarers-quartet/

http://bookviewcafe.com/blog/2010/03/21/starfarers-the-miniseries-cast/

Citations:

McIntyre, Vonda N. University of Oregon Special Collections (Eugene, OR), Joanna Russ Papers, “Correspondance with Vonda N. McIntyre, 1970-1988,” Box 8, Folders 18-25. Accessed October-December 2013.

McIntyre, Vonda N. University of Oregon Special Collections (Eugene, OR), Ursula Le Guin Papers [RESTRICTED], “Correspondance with Vonda N. McIntyre,” Box 22, Folders 11-14. Accessed November 2013.

Vonda McIntyre’ Star Wars Villains

I originally set out to search for fan art specific to either Dreamsnake or Superluminal but following the review of my last article, it makes more sense to follow it up with her work in the major franchises (also – fun fact – if you google image “dreamsnake fanart” so many pictures of My Little Pony come up.)

McIntyre got 2/7 villains in Darthrand’s Seven Star Wars Villains You Don’t Know!

Star Trek: A Natural Continuation of McIntyre’s Feminist Works

In Changing Regimes: Vonda McIntyre’s Parody of Astrofuturism, De Witt Douglas Kilgore is responding to the claims of Frances Bonner that feminist SF authors whose works were published in the 1960’s and 1970’s have reverted to writing in a “masculine genre.” Instead, Kilgore argues, using Vonda McIntyre’s work as his primary focus, that it was rather a form of tactical feminism using the conventions of Cold War astrofuturism as a thoughtful reengagement in response to critics who sought to limit the impact of the feminist speculative fictions. “McIntyre’s recent work can be read not as the abandonment of her earlier feminist project bus as a refusal to accept its containment within a subgenre” (261). As I understand it, astrofuturism is the idea that humanity will reinvent itself when it achieves its destiny in space; which, in itself, could reflect any political mindset/values. However, it has often been associated with the reproduction of militaristic colonialism.

Kilgore then breaks down McIntyre’s subversiveness in the Star Trek and Star Farer series citing as one example amongst many, her Star Trek novel The Entropy Effect in which “a security chief, a starship captain, a defense attorney, and a brilliantly inventive engineer represent the types of women who make up McIntyre’s future” (261). Why would Star Trek be a worthwhile site of feminist discourse if anchored in patriarchal narratives? Kilgore argues that “while the feminist/anti-racist politics of the 1960s and 1970s made it possible to talk seriously about racism, sexism, class bias and other antagonisms, they did not negate the imaginative power of these regimes within sf’s mainstream” (260). I find myself easily convinced that McIntyre did try to bring in a certain amount of subversiveness in these texts as she herself expressed in class last week. “Poor Kirk, he always gets turned down in my novels.” (Vonda McIntyre, UO – Nov 7th.)

Kilgore, De Witt D. “Changing Regimes: Vonda McIntyre’s Parody of Astrofuturism.”Science Fiction Studies 27.2 (2000): 256-77. Print.

Why Ygor? [Vonda]

Dear master, good master,

It seems like I have a lot of questions and very little time. This is a painful contrivance. I’m sure I won’t get a chance to ask many of them tomorrow, a lot wouldn’t apply unless someone had read your letters and I don’t want to waste their time. I put some thought into these, though. Hopefully, the chance comes later this week, some time. I feel that this entire term (esp. working in the archives), we have been less learning and more developing questions about fiction and authors that yearn to be answered. I want to know.

In your early 20’s, you left your PhD program in genetics at UW and began writing in order to make a living. At that time, did you think writing would be your career, or something to do with your BA in Biology? At what point did you consider yourself a professional writer, as opposed to an amateur? What did that change mean to you?

How did your relationships with other members of the SF community change as you made the transition from fan to peer? (Esp. Russ, Le Guin, Tiptree, etc.)

Something Kelsie pointed out was the parallel between your apartment in Seattle getting robbed in college (and your files taken) and Snake having her journal stolen by the crazy in Dreamsnake. Did real life inspire fiction here? How do things in your own life inspire your writing?

So, as a young author, you didn’t hire/find a literary agent until after you won your first Nebula Award in 1973. Was this a conscious choice? … I also saw that you continued to handle a lot of business affairs as an anthology editor and workshop organized even afterwards. Do you like the financial management aspect of writing, or was this a bit of Northwest do-it-yourselfism?

As a long-time resident of the Coast Range, how were you affected by your experience living at the Le Guin Cabin in Rose Lodge? … Did you spend more time there after the mid-1970s?

You spoke a lot with Joanna Russ about your take on the feminist movement in the 1970s as a young woman. What do you feel has changed for women today, both at the university-level in general and in the sciences specifically? … What about for beginning female authors?

More so than a lot of the other authors we’ve read in our class, you have worked in Hollywood and in television. What motivated you to take your work in that direction? Was it your influence from Harlan Ellison? … Would you care to talk a bit about the upcoming production of The Moon and the Sun?

Speaking of Harlan Ellison, I was really surprised in one of your letters to see that you came up with the term “Speculative Fiction” to describe his work. Is that correct?

You seemed to collect a lot of hotel stationary. What was the best you’ve ever found?

Hopefully, the opportunity arises sometime soon.

Sincerely,

Quintin Kreth.

Dearest Vonda

Dearest Vonda,

This weekend I attended a party for the first time in months. I hardly knew anyone there, and no one talked to me except one guy who walked up, exposed his abs, and asked me about their sex appeal. My response of “all bodies are good bodies” did not deter him, and I ended up leaving early. A while ago, you said that you hoped things would be different by now (see Quintin’s last blog post). We’ve come a long way thanks to awesome ladies like you, but I feel I still struggle against sexism on the daily. Does that disappoint you? Or, since you’ve lived the years in-between, seen the challenges women have faced, do you know why we seem stuck? It’s an uphill battle, of course, that will not be easily won.

I have many other questions for you, about everything from your favorite color, to why you left genetics, to what you think about Doctor Who, to your favorite breakfast food, to your childhood in the Netherlands. My research through your letters and books and Internet comments has led me to believe all your answers would be witty and eccentric. I can save those for later, but I’d love it if you answered just this one: what are you reading right now? I’m always looking for suggestions.

Watching you learn and grow through your letters has been fascinating, as I’m in a similar period of growth and tumult. It’s partially comforting, to know most people experience something like this. It’s also eerie, to read over your words regarding isolation from my empty studio apartment, experiencing the joys of introversion, tainted by the sting of unexpected loneliness, that I imagine you may have felt.

Like a bridge across time, your words to Joanna Russ have connected me to a person I have never met – Vonda of 1972. While I regret not getting the chance to meet her, I can’t imagine how freaking cool Vonda N. McIntyre of 2013 will be. Thank you for everything you’ve done for sci-fi, for women, and for this class.

Warm regards,

Kelsie

The Moon and the Sun: A Different Kind of Sci-Fi – a book review

Science fiction fans will be surprised by Vonda N. McIntyre’s The Moon and the Sun, for it is not your typical science fiction book. Instead of aliens, super-techy intergalactic transportation or the awesome laser gun, The Moon and the Sun, takes place in seventeenth-century France, at the court of King Louis XIV – where court rituals, court intrigue, irksome, ‘all-knowing’ men, romance, natural philosophy, extremely long and cumbersome French titles, and mermaids, I mean, sea monsters, abound. Fans of McIntyre, or simply alternate history fans and romantics who love an intelligent, compassionate heroine will devour this book, all 416 pages, yelling in outrage at the men who belittle our heroine and sighing with delight when she finds love.

Science fiction fans will be surprised by Vonda N. McIntyre’s The Moon and the Sun, for it is not your typical science fiction book. Instead of aliens, super-techy intergalactic transportation or the awesome laser gun, The Moon and the Sun, takes place in seventeenth-century France, at the court of King Louis XIV – where court rituals, court intrigue, irksome, ‘all-knowing’ men, romance, natural philosophy, extremely long and cumbersome French titles, and mermaids, I mean, sea monsters, abound. Fans of McIntyre, or simply alternate history fans and romantics who love an intelligent, compassionate heroine will devour this book, all 416 pages, yelling in outrage at the men who belittle our heroine and sighing with delight when she finds love.

The Moon and the Sun, published in 1997 by Pocket Books (a division of Simon & Schuster Inc.), follows twenty-year old Marie-Josèphe de la Croix, lady-in-waiting to Mademoiselle d’Orléans, Louis XIV’s niece. Marie-Josèphe, an ambitious and curious young lady, loves mathematics and finds natural philosophy fascinating. When her brother, Father Yves de la Croix, returns from a scientific expedition, he brings back with him the endangered sea monster, whose flesh is rumored to give immortality – something King Louis XIV would love to take a bite of. Marie-Josèphe gets the chance to be her brother’s assistant, sketching the dissection of the male sea monster and feeding the live female one, which Marie-Josèphe decides she will train and tame. As Marie-Josèphe juggles her lady-in-waiting duties, her chores for her brother and the sea monster, and composing a cantata for the king, Marie-Josèphe finds herself at odds with some members of the court, especially from the men, who try to treat her as a plaything and scorn her for her interests in math, science, and music composition (all things women could never, should never do, let alone excel at). Marie-Josèphe has to endure all of this while trying her best to follow all of King Louis’s complicated rules of etiquette. Thankfully, the respectful Count de Chrétien – one of the king’s most trusted advisors and the epitome of etiquette and refinement – is there to help Marie-Josèphe. Soon, Marie-Josèphe comes to realize the captive sea monster is not a creature, a monster, but a sea woman, one with language, history, intelligence, who yearns to be free. As the only one capable of understanding the sea woman, Marie-Josèphe, with the help of Monsieur de Chrétien, must convince the youth-seeking king to release the sea woman even while others, including her brother, write her off as ridiculous and infatuated with her ‘pet.’ In the end, Marie-Josèphe has no choice but to defy her king, her brother, even His Holiness, Pope Innocent XI, in order to do what is right and save another ‘human’ creature.

One of the major themes in this story is the treatment and roles of women, especially women inclined to the sciences. Colony-raised and fresh from convent school, Marie-Josèphe is an innocent, a fact that the other men try to take advantage of. Previously, Marie-Josèphe had thought many men, such as the Chevalier de Lorraine, to be handsome and kind. Instead, Marie-Josèphe discovers these men are crass, treating her as just another frail object to be played with. The chevalier even holds Marie-Josèphe down as she is bled because she is ‘hysterical,’ though Marie-Josèphe begs him not to let them bleed her. In one particularly horrifying scene, Marie-Josèphe is chased, pinched, taunted, and clothes ripped by three other male noblemen (men Marie-Josèphe had previously thought handsome and kind) while participating in the King’s Hunt. Marie-Josèphe is restrained by the role the court places on women, just as the sea woman is held captive and thought incapable of intelligence beyond base primal instincts. As the Pope says, “Women should be silent and obedient.” That is their lot in life, and Marie-Josèphe is trying her best to not be contained by that belief.

Expanding from that, McIntyre also explores what constitutes humanity and intelligence. The utter refusal of most of the characters to acknowledge the sea monster as an intelligent, conscientious being instead of a dog is astounding. The court’s utter incapacity to accept the sea monsters as another culture and race and give the sea monster due respect is cruel. As a result, the sea monster, once free, declares war on the human race if ever they should cross her path.

This leads us to empowerment from freedom– or the hint thereof. The sea monster character is reflected in Marie-Josèphe herself, a captive in her role as a woman. Marie-Josèphe, though unable to physically fight back at her tormentors, still manages to bring herself to defy them; in doing so, her punishment unwittingly releases her to pursue her dream, leaving her free to explore her love of natural philosophy. Haleed, Marie-Josèphe’s slave, also finds empowerment from freedom, even though she knows not how her life will pan out.

Marie-Josèphe’s fight against the constraints men have placed on her reflects the many other heroines featured in feminist science fiction. The terrible treatment of women is what many feminist authors are fighting against – what their heroines are fighting against, and what everyone, should be outraged about. McIntyre’s well-researched depiction of the French court shows that the fears of feminists are not unfounded. The undermining of women has happened for centuries; what we need to remember is the immorality of such treatment – of woman and sea people.

McIntyre’s writing and research envelop you into seventeenth-century France. You have no choice but to be sucked in and laugh at the outrageous fashion of fontanges (Google it, really). Though be warned, the French nobility have long, multiple titles, and though McIntyre tries to abbreviate, using M. and Mme. for Monsieur and Madame, names and characters can become confusing. Thank goodness McIntyre includes a character list of who’s who.

And for those who do not know, The Moon and the Sun has been chosen to be adapted into a movie, starring Pierce Brosnan next year. I, for one, cannot wait.

Dreamsnake by Vonda N. McIntyre

WHEN (this was published)

Dreamsnake, written by Vonda N. McIntyre, was published in 1978 by Houghton Mifflin Company. McIntyre based the novel on her novelette, “Of Mist, Grass, and Sand,” for which she received the Nebula in 1973, and a Hugo nomination in 1974. In the 70s, McIntyre witnessed both the women’s liberation movement and the rapid development of genetic knowledge and technology. To write a story with a dynamic heroine, systematic gender equality, nonexistent rape culture, uninhibited casual sex, homosexuality, and polygamy, was and still is an incredible feat. McIntyre was recognized for her efforts, as Dreamsnake won the Hugo in 1978, and the Nebula in 1979. Dreamsnake was only the third book featuring a female protagonist to earn the Hugo. However, the book fell out of favor and has not been in print for over a decade.

WHO (should read these 277 pages)

Anyone with a healthy sense of adventure, a fondness for reptiles, or an interest in the medical field would find Dreamsnake by Vonda McIntyre enthralling. I would recommend it to high schoolers and adults prepared for strong liberal sexual undertones, focused on values of consent, equality, and safety. But really, if you have Ophidiophobia, don’t read Dreamsnake unless you’re serious about confronting your fear.

WHAT (happens between the pages)

A young woman named Snake sets out through the treacherous landscape of post-apocalyptic Earth to develop and utilize her skills as a healer. One of the most useful tools for a healer is the snake, ranging from average sand vipers, to albino cobras that can catalyze medicines and vaccinations, to alien hallucinogenic dreamsnakes. The death of Snake’s dreamsnake, Grass, sets off a chain of events that sends our heroine on a perilous journey to the technological walled city of Center and beyond. Along the way she heals the sick, battles for the weak, and meets many fascinating individuals, like Merideth, an ambiguously gendered polygamist jeweler, Melissa, a scarred twelve-year-old horse tender, and Arevin, who is not the expected knight-in-shining armor love interest. The vivid and diverse set of characters, the believable yet imaginative biological extrapolation, and the dynamic, inspiring, protagonist carry the reader through a memorable adventure in pursuit of knowledge, compassion, and dreamsnakes.

WHERE (we can fit this book into our understanding of the world)

Heavily influenced by women’s lib movements and discussions she was having about gender, reproduction, equality, McIntyre created a feminist utopia in the world of Dreamsnake. This influence is felt in the systemic gender equality that pervades the setting, as all individuals can own property, participate in neutral casual sex, and enter into fluid polygamous partnerships. Due to the biological ability to control fertility (biocontrol), men and women share the burden of prophylactics, and consent precedes all sex. Sexual assault is abhorred in society; it is unclear if they even have a word for rape. Things function supposedly so people “can all be as free as possible most of the time, instead of some [sic] being free all the time,” though slavery persists in isolated areas (McIntyre, 61).

McIntyre also issued statements on science with her passages on genetic manipulation and cloning. People who live in the advanced city of Center hold fear and disgust for practices of cloning and mutation, whereas the healers genetically manipulate organisms and manage to maintain balanced, caring relationships with them. McIntyre humanized science a bit there, showing individuals as the driving force behind discovery and having the power to affect the implications of their work for the better. She also demonstrated science’s effectiveness at bringing people together with her description of the healers’ community as a place for gathering to further peace and knowledge.

This healers’ community is shown to have faults, however, in its isolationism. In fact, almost all groups in Dreamsnake share this fault, most likely developed as a coping strategy for the lack of interpersonal trust in harsh post-apocalyptic conditions. Arevin’s clan, for example, had a practice of withholding their given names until an intimate connection is created. In another case, isolation from the healers’ knowledge led to the death of Snake’s dreamsnake. Center is also isolated, which created an ignorant population, vulnerable outside the walls of their city. As McIntyre reminds us, “[Snake’s] people, like all the other people on earth, were too self-centered, too introspective. Perhaps that was inevitable, for their isolation was well enforced. But as a result the healers had been too shortsighted” (255). McIntyre illustrated how people are shaped by forces outside their control, and can only make choices within environment boundaries. But in this case, choices led to isolation of knowledge and technology, which inhibited the growth of humanity. This proved a detriment to Snake’s society, and many were hurt because of a stubborn refusal to share.

WHY (you should read this)

Mostly because it’s magnificent, but also to prove this reviewer wrong:

“Why do female science fiction authors write like female science fiction authors? Do they have to be so stereotypical? Their ability to write characters is shit, which is extra annoying because women are supposed to be so fucking empathetic. “Dreamsnake” is written like some sort of personal fantasy of a science fiction high school loner. In it, the female heroine is a healer in a post-nuclear warfare Earth. She goes from place to place, helping people, but none of the places and events are interesting. In it, there is a muscled hero with him acting all chivalrous and completely in love with her, that…just fuck. You know what, in my personal project of reading every Hugo winner, I have realized that every science fiction book awarded to a female author has been shit and I can only rationalize it with the fact that the judges were probably huge nerds that probably felt that by giving high points to the female authors, they might get to fuck them. Even if the female authors looked like science fiction aliens…” — Goodreads.com

HOW (you can read this book)

Dreamsnake is available as an e-book:

http://bookviewcafe.com/bookstore/book/dreamsnake/

McIntyre, Vonda N. Dreamsnake. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1979.

Abedi, Mohammad Ali “Dreamsnake.” Goodreads. Goodreads Inc., 1 Aug. 2013.